Last winter, admirers of Philip Larkin gathered in Hull, England, hosted by The Philip Larkin Society, to celebrate the centenary of the poet librarian’s birth. An ocean away, I had Larkin on my mind. Only a week before, I’d quoted his “This Be the Verse.” I was not alone. Bowie, Lemony Snicket, The Talking Heads, the Roy family’s therapist, in “Succession,” all and more have shared Larkin’s catchy, trenchant lines.

It was a Larkinesque day, low-ceilinged and gray, wet leaves the color of blood pressed into the ground after a night of wild rain. With a familiar touch of anticipation, I’d hit Send. And, as expected, the friend on the receiving end quickly responded to Larkin’s darkly comic embodiment of grief with laughter and gratitude gifs, feeling, perhaps, for a blink, a sliver of consolation.

While I appreciated Larkin’s deployment of fuck’s force decades before researchers demonstrated that swearing aloud increases pain tolerance, I’d also felt ambivalence, and a tinge of loss, the matter of this poem, its considerable heft slyly tucked into mirth, eroding. Why, 51 years after it first appeared, in New Humanist, a publication of the Rationalist Association, founded in 1885 to promote “reason, science and humanism and standing up to irrationalism and religious intolerance,” was I sharing “This Be the Verse”?

Scholars think Larkin wrote “This Be the Verse” after an extended and difficult visit with his mother, Eva. As for Larkin’s father, Sydney, he was an admirer of Hitler who attended two Nuremberg rallies and demonstrated both adoration and vexation with his wife and his children, Philip and Catherine, who was ten years older. Their mother, Eva, reportedly suffered from bouts of depression and was treated with electric shock therapy for what scholars suggest resembles emotional abuse.

Larkin died in 1985 at age 63. Today the subject of a monthly produced by The Philip Larkin Society, called “Tiny In All That Air,” he was a gifted and ambitious writer, a friend and teacher and mentor, and also, by accounts, a difficult man. At times sexist, racist, an alcoholic, a recluse.

“An asshole,” one of my brothers said when I called him. “People are still assholes,” he observed. “Lots of them get podcasts.”

We’d been handing “This Be the Verse” back and forth since becoming parents ourselves, lines like polished stones, soothing and solid in our clutch. Can we not fuck up our kids? we asked ourselves and each other. Did we fuck up already, having kids of our own?

Misery, especially the kind handed down man to man, is not so crystalline.“This Be the Verse,” the poem, appears to stand up to time. Its opening lines are clear as a crack to the head, even more quotable, it is argued, than the first lines of Larkin’s renowned “Annus Mirabilis”: “Sexual intercourse began/In nineteen sixty-three/ (which was rather late for me)…”

But misery, especially the kind handed down man to man, is not so crystalline. Meaning “This Be the Verse,” while surprising and even, arguably, mysterious, is not accurate. And, in light of Larkin’s directive—“don’t have any kids yourself”—it’s not hard to find oneself tilting toward Elizabeth Bishop, who thought of accuracy as one of the best qualities of poetry, alongside spontaneity and mystery.

Misery might be handed down man to man, adult to child, and it might represent a gradual slipping in time, but misery does not deepen “like a coastal shelf,” the way Larkin described. The coastal shelf consists of bedded layers, discrete and discernible when extracted for view, whereas intergenerational trauma, a cycle Larkin describes when he writes “Man hands on misery to man,” is a murky thing. One minute you’re standing on solid stone, the next you’ve lost all ground and are sinking in sucking, silty mud, gasping for air, fearing you will be swallowed alive.

Sticking with the geological metaphors, a sediment routing system is a more precise corollary than a coastal shelf, if, poetically, a sinker. I think of a paper I discovered after a kayak trip along a winding river with my relentlessly questioning kids, published in 2008 in Nature, by the geologist and renowned sedimentary system expert Philip Allen. “One can imagine,” this Philip wrote in “From Landscapes into Geological History,” “tracking the trajectory of a single grain of sand from its source in mountain headwaters to its sink in a river flood plain, delta or the deep sea.” Imagine each grain of sediment—more than 20 billion tons’ worth each year—with its own “trajectory,” its own “time in transit,” erosional source to depositional sink, before solidifying in the earth, where it might someday be uplifted yet again, de-formed, dissolved, or redeposited, by monsoon rains, earthquake, volcano, or imperceptible, inexorable tectonic shifts.

Now imagine, instead of tracing grains of sand, you are tracing instances of harm. Time transforms sediment from billions and billions of unique grains of matter into literal stone, just as time transforms billions and billions of instances of adverse childhood experience—of neglect, pain, cruelty, violence, oppression—into our bodies. Via mechanisms we are only just beginning to fully understand—historical trauma, intergenerational trauma, institutional trauma, personal trauma—each moment of misery handed to us from the previous generation courses into our genes.

I’ve reported on harm and prevention, but I’m not a scientist, so, wondering whether I’d dug myself into a hole here, I talked to Alexander Densmore, a professor of geology at Durham University and a friend and former colleague of Allen’s. I’d read the warm tribute to Allen he coauthored in 2021. “His students and colleagues will remember him perched by an exposure,” it read in part, “deftly sketching it in his notebook, and his habit of asking ‘Are we happy?’”

“Yes,” Densmore confirmed when asked whether Larkin’s use of coastal shelf as metaphor was faulty, “it’s not that simple.” Densmore elaborated. “By zooming in on just one thing as unchanging”—a delta, say, or a coastal shelf—”you’re missing out on all the complexity.” Turbidity currents, for instance, “can flow for months in huge undersea rivers that go and go and go, and we have no idea exactly how it is influencing geology because it’s happening under the ocean.” At the same time, he continued, “the sea level is rising and falling and rivers are flowing. And then there are times when the sea is coming back in and bringing sediment with it.” In other words, the cycle is not fixed, immovable, and inevitable. “With all of the complexity and dynamism…all of these things changing at once, there are many possible outcomes and trajectories not just for an individual grain of sand but for the system as a whole.” We infer great things, he said, vast mountain ranges or undersea valleys, but “you’re feeling your way in the dark.” As for Allen, “He was ultimately humbled by the complexity of the natural world. He never forgot that we were very small.”

If we agree that the project at hand is less misery and more care, the fact that misery does not accrete in discrete layers like a coastal shelf, that the cycle of intergenerational trauma runs more like a sediment routing system is less important than another fact: Man handing down pain to the next man is not destiny. Repeat, repeating harm is not a rock-hard law of the land. It is not inevitable. Misery as coastal shelf is an antediluvian myth. And it is this idea, as much as any predictable revelation about Larkin’s flawed humanity, a man both misery-forged and misery-producing, that inspires a stone tossing at the surface of “This Be the Verse.”

Research demonstrates the higher the number of adverse childhood experiences one has, the higher the risk of chronic physical and mental health conditions—heart disease, lung cancer, depression, and much more—later in life. But research also demonstrates that we can use all sorts of behaviors and interventions to reorient the system. “People believe history is unchangeable,” Dr. Nadine Burke Harris said when we discussed “This Be The Verse” during a phone call, “because that’s been their experience.”

Burke Harris, author of The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-term Effects of Childhood Adversity, knows as much as anyone on earth about misery’s trajectory, and how it settles in both our individual human bodies and our communities. While serving as California’s surgeon general from 2019 to 2022, Burke Harris spearheaded one of the country’s first state-wide programs aimed at systems-level change in how we approach the effects of trauma. Since then, that trailblazing program has gotten some 20,000 doctors trained, 900,000 children and adults screened, and state leaders in housing, emergency response, transportation, education, and early childhood care cooperating in an effort to saturate their agencies with policies and strategies demonstrated to identify and treat the effects of the kind of misery that’s handed down man to man, or in Burke Harris’s chosen medical term, “toxic stress response.”

“High doses of cumulative adversity experienced during critical and sensitive periods of early development, without adequate buffering protections of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments, can become ‘biologically embedded,’” she has written. Once this toxic stress response to harm is embedded in the body, it disrupts brain and organ development systems and increases the risk of disease and cognitive impairment, “well into the adult years.”

But, Burke Harris said when we talked, “the knowledge we have now, and the science we have now, shows it is treatable.” It is not only harm that leads to illness, but harm in the absence of care. Epigenetic markers can actually change in children when they receive care, whether from a biological parent or others, especially if they experience that care and love over time. “If we can tip the scales, so that kids accumulate more positive than negative, then time is working in our favor,” she says. “The younger we are, the more vulnerable we are. But also, the younger we are, the greater the potential for really deep healing when the interventions happen.”

The experience of positive childhood experiences wards off misery, tempers it, pushes it up and out, according to a 2019 study published in JAMA Pediatrics. The odds of having depression or poor mental health overall as an adult, researchers found, were 72 percent lower for participants with higher levels of positive childhood experiences.

What we have now, Burke Harris said, “are the tools to break the cycle, reliably, repeatedly.” She has identified seven granular, research-based strategies that prevent the human-to-human hand-off of misery: sleep, exercise, time in nature, nutrition, mindfulness, mental health care, and healthy relationships. The tool she uses most? “Walk and talk. Exercise combined with talking with someone.”

Ideally, she said, everyone has access to the tools for healing. To good doctors who can help them understand how their adverse childhood experiences and family history affect their risk of harm. To food and housing and job security, education and safety. Ideally, everyone who needs and wants it can get into therapy, not to gather up surface praise, but to dig deep for healthier ways to be in relationship with other people and, critically, ourselves. In therapy, Burke Harris said, “you can work together to create a plan for prevention.” A plan to stop handing on misery.

Cycles that might seem inevitable can evolve in unexpected ways and lead to unexpected outcomes. Poems, too.Ideally, we all work to shore up policies and institutions that support collaboration and care, places, whether a family, neighborhood, school, or country, where people pull together and do their damndest not to repeat, repeat the harm. “The real work,” she said, “is to change societal outcomes.”

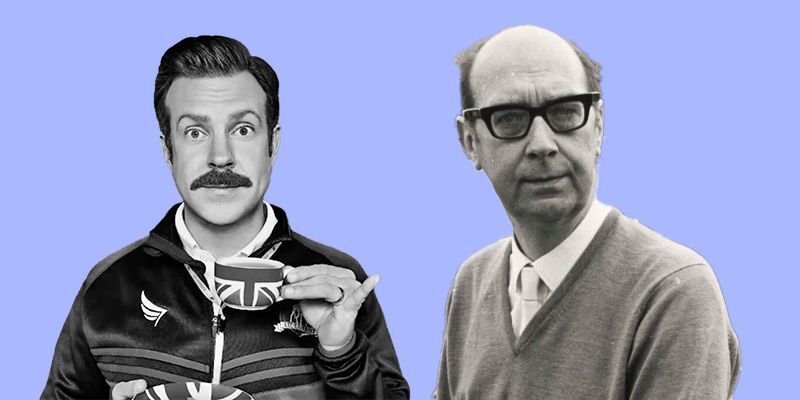

Unquestionably, it is a good time to pass along the revelations and research of Burke Harris, and others who are pushing back on cynical acceptance and imagining a different trajectory, while also, perhaps, cracking a grim smile alongside Larkin. There’s Stephanie Foo, Judith Herman, Resmaa Menakem, Bessel van der Kolk, and others too numerous to list in full here, and, well, yes, says Burke Harris just before we hang up, there is now also “Ted Lasso.”

“How has nobody emailed me about this?” Burke Harris recalled wondering as she’d watched. The show’s communities are cooperative and inclusive, with characters who step up against bullies and bigots, who do not tolerate abuse and harm, of anybody, regardless of identity or position. There’s a men’s group that aims to nurture healthy relationships, she observed, the juxtaposition of one dad who is verbally abusive to his son with another dad who lifts his son up, and all sorts of people who decide to try therapy, including Ted. “It feels so different than what we would have seen even ten years ago,” Burke Harris said. “It’s beautiful.”

Not long after Burke Harris and I talked, I was watching the show myself, when, wait, there, again, eighteen minutes into the eleventh of final season’s twelve episodes, was Philip Larkin. Ted’s mother has come from the U.S. for an extended, difficult visit, and Ted has just excused himself from their table at Mae’s pub. He stands at the pinball machine pretending to play, collecting himself.

Hugging serving tray to chest, Mae approaches Ted, her nimbus of white hair glowing.

“They fuck you up, your mum and dad./…,” Mae begins, no introduction, no title. “They may not mean to, but they do…/.” Her voice dusk-low, the poem unfolds. “But they were fucked up in their turn/ By fools in old-style hats and coats,/…” Mae lands Larkin’s final lines as clear as a crack to the head. “Get out as early as you can,/And don’t have any kids yourself.”

But, as anyone who’s watched the show knows, it’s too late for Ted. Ted was fucked up in his turn, he knows. He drank up all the faults they had, those fucked up fucks, his mum and dad. And he might fuck up his son, too. He lives an ocean away, and Ted anguishes over the question of whether to return. It won’t be until the last episode that Ted tells his Mom to fuck off, for burying the facts of his father’s death, and then suggests that she, too, might find therapy helpful.

Maybe, as one critic put it, Ted Lasso’s offering is a “fantasy,” in the words of the show’s Peabody Award citation, “the perfect counter to the enduring prevalence of toxic masculinity, both on-screen and off, in a moment when the nation truly needs inspiring models of kindness.” And, as the geologist Philip Allen put it, “We are right to be suspicious of oversimplistic interpretation.”

But, maybe, it also offers an imagining. As Allen concluded, our time “requires a new conversation, so that the epic poem of Earth history can be better read and learned from.” Sure, Ted Lasso does not represent a tectonic shift, but it has in its own small way pushed towards a new conversation, one aimed at slowly dissolving America’s bedrock violence and banding us together instead. In light of ascendent white nationalist ideologies and communities, increasingly mainstreamed threats of political violence, an unprecedented mental health crisis for kids, and growing partisan hostility, why not create more templates for change? Together, we bear misery, shifting and roiling, riverine.

Is it time to stop sharing “This Be the Verse”? Who can say? Abuse feeds on denial and non-engagement. Acknowledgement and recognition of harm, of the fuckers and the fucked-up on the individual level and, perhaps more critically, on an institutional level, can be a tool of healing and change. Cycles that might seem inevitable can evolve in unexpected ways and lead to unexpected outcomes. Poems, too.

“Factual mistakes can be portholes to intention,” Larkin scholar and former U.K. poet laureate Andrew Motion said when we talked. Today, we know that the cycle of abuse can be broken, and that Larkin’s expression, in Motion’s words, “of the ungovernable aspects of life that propelled him” still carries both levity and weight. “This Be the Verse,” he said, “is a poem that didn’t see its future.”

Perhaps someday we will know, if not all, more of the processes that govern our human systems: love and care, abuse and harm, our individual and shared resilience and intelligence. That would be enormously gratifying. Certainly, Burke Harris and a legion of others are working to develop and share their knowledge, in some 15,000 scholarly works related to adverse childhood experiences and intergenerational trauma. Until then, we will have tried to know something different, something better; we will have worn out our old-style coats and hats and died trying.

True to his word, Larkin never did have kids himself. In “Love Again,” a poem published posthumously, he wrote:

And say why it never worked for me.

Something to do with violence

A long way back, and wrong rewards,

And arrogant eternity.